|

When Kommer Kleijn (1959) was preparing to shoot his first

movie,

the Gulf War just started. The film industry in Belgium was in

ruins, and Kleijn’s moment seemed gone. Rather than letting it

frustrate

him, he decided to take advantage of the time to study visual effects,

animation and 3D. Now, his telephone doesn’t stop ringing, and he is

overwhelmed with constant requests for guidance on stereographic films.

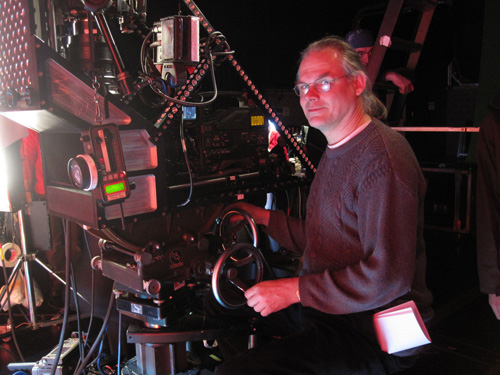

Director

of photography Kommer Kleijn S.B.C. (photo:

Bart van Broekhoven)

Director of Photography, VFX cameraman, stereographer and

technologic consultant; these are the self-ascribed qualifications that

Kommer Kleijn lists on his website, www.kommer.com. The list of

qualifications can easily be lengthened, to include Visual Effects

Cinematographer, Motion Control Cinematographer, Special and Large

Format Cinematography. By now, Kleijn‘s specialties are not to be

counted on one hand. The sprightly fifty year old sits relaxed in the

luxurious Sheraton Hotel in Schiphol. His striped jacket hangs casually

on a white designer chair. Very calm, he animatedly answers the

questions, while his blue eyes sparkle behind his glasses. One could

hardly imagine that his plane for Brussels leaves in two hours.

Director

of photography Kommer Kleijn S.B.C.

This

Belgian of Dutch origin has grown accustomed to a lot of travel in the

past few years. At the moment he divides his time between his work as

stereographer, teaching in two Belgian film academies and giving

stereography workshops to professionals around the world. He used to

travel around the world as a member of Technical Module of the EDCF

(European Digital Cinema Forum), and president of the technical

committee of Imago, the European Federation of Cinematographers.

Kleijn’s

expertise is in high demand. But it has not always been like this.

Belgium

After taking his last high

school exam in 1978, Kleijn signed up for the Film academy in

Amsterdam. “I was working with photography and I just didn’t want to

end up doing what my parents were doing. My mother is a pianist, my

father was an engineer. According to David Samuelson in his Hands-On

Manual for Cinematographers, a cameraman is half artist, half

technician”. That was exactly my case, so in retrospect I have made

them both happy”.

Shooting

3D on 35mm film for the Dutch pavillion on the Floriade universal expo

2002

He

was not accepted In Amsterdam. “I was probably talking gibberish, I was

so nervous.” Taking his sister´s advice, he turns to Belgium for

answers, where he takes admissions exams in two film academies. He is

accepted in to both of them. His preference goes to the French language

academy

INSAS (Institut National des Arts de Spectacle et Techniques de

Diffusion) in Brussels, because the work of his teachers Ghislain

Cloquet ASC and Charlie Van Damme AFC appeals to him. “I totally

bloomed in Belgium. During my studies I made very profound friendships.

Afterwards, I never felt the need to leave the country”.

Gulf War

After the academy, Kleijn

follows the classic road of clapper loader, (among others “Een Vlucht

Regenwulpen" and "Menuet"), first assistant, cameraman for thirty short

films and cameraman second unit. Logically, these should lead to jobs

as DoP of long films. But it doesn’t work that way. The Gulf War starts

and the film industry in Belgium is in ruins. To be able to take care

of his needs, Kleijn, -always interested in tele- and data

communication, goes to work part time in a computer shop. He also makes

corporate films and commercials (VFX and DoP), and expands his

technical knowledge independently. He specializes in visual effects,

blue screen and composition photography. Also stop motion and motion

control have his attention, just like stereography and large formats,

like IMAX.

Thanks to his technical and electronic background, he also gets

involved in the development of new camera systems. He conceived and

designed the “Animoko”. Specialized in stop motion. “Animoko” is the

abbreviation of Animation Motion Control, actually Animoco, but I

changed the c into a k because of my name.”

Kommer

Kleijn S.B.C. with his Animoko Motion Control Rig

After the Gulf War the film industry in Belgium recovers very

gradually. “For about six to seven years there was no place for a

"jeune

premier", as we call them. The producers first asked the experienced

cameramen who were sitting on the sidelines twiddling their thumbs”.

Kleijn´s moment to debut as a film DoP seemed over. The corporate films

and commercials that he made were not satisfying him. “I was looking

for challenges, and I ended up with increasingly complex technical

things. That is how I became a man of many specialties. I got the

reputation from producers, who thought, “if you get a script and think:

how in God’s name am I supposed to do this? Call Kommer!” I got all

kind of weird things on my plate.

3D

That is also how he got his first job

in 3D, in 1998. A Japanese amusement park commissioned him for Alice in

Digital Land; an interactive 3D, image synthesis, virtual reality,

live-action 26 minute film. The audience could vote 10 different times

about how the story should go on. As no 3D camara is available, Kleijn

starts to design a 3D camera himself, in

cooperation with a company, based on cube cameras from the medical

world, 7.7 Fuji zoom lenses and a mechanical coupled focus. “The first

films all had a green screen, you were then able to make corrections.

We worked with a virtual studio. The sets were virtual, the leading

actors real, the co-stars in CGI/image synthesis. It was a fantastic

laboratory experiment.”

More 3D projects followed, among them a

corporate film for Gasunie and a short film for the Dutch pavilion at

the Floriade. Kleijn was also asked, as a stereographer, to supervise

on a

Russian film. It was a top production, with a crew of 150 people, but

after three days it had fallen apart. Nowadays his telephone is red-hot

for stereographic commissions, which continues to amaze him: “For

twelve years I made one 3D-film a year for a couple of madmen. Now it

is surprisingly trendy. All of a sudden it turns out I can do something

that almost

no one else can do”.

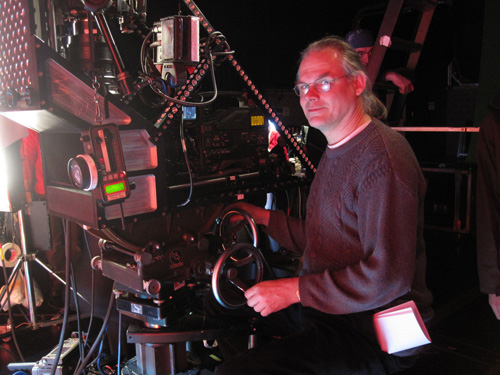

Director

of photography Kommer Kleijn S.B.C. shooting a 3D commercial

“In my work as a stereographer, my experience as a cameraman

is a

huge advantage. As stereographer and cameraman, you don’t only take

into account the fact that the audience shouldn’t get a headache, but

alsothat a story needs to be told. Furthermore, you understand

the

relationships on the set: in disagreements the director is the boss,

then the cameraman and finally the stereographer. People that have been

educated only as a stereographer are not always aware of these

differences. You also know that you have to find a way to work fast, so

that you are not fiddling for half an hour, otherwise the director and

the actors go insane. That is the most important part of 3D, to serve

both the film and the story, and to do it in smooth cooperation with

the rest of the crew. You also shouldn’t forget that ultimately

it is all about storytelling fo the audience and giving them a good

experience.”

Mister Frame Rate

Since 2007 Kleijn

has been a member of the Imago technical committee. Among other

things, in this capacity, he has kept himself intensively busy and

successful with the implementation of new standard frame rates

in digital cinema projectors. “Frame rates have really become a thing

for me. At the SMPTE in America I am often nicknamed Mr. Frame

Rate". I am devoted to

projection. My love for cinema begins in the theatre. I have always

been magically in love with the cinema, and the projector is a

key

element. Because in the end, that is the thing: you can make the nicest

pictures in the world as a cameraman, but if the projector can not

reproduce them, then you have nothing.”

<>Director

of photography Kommer Kleijn S.B.C.

In

his student days, Kleijn was already ‘chief projectionist’ in a small

theatre where films were shown twice a week. “Cinema projection is

almost

sacred to me. Since 2002 I have had a 3D projector at home, a huge

mastodont, imported from Boston”. Electronic projection has always

indirectly interested him. But as soon as the discourse about digital

projection begins, he cannot follow the developments from the

sidelines. “The ITU (International Telecommunication Union) proposed in

2002 to use HDTV-standards in cinemas. The whole camera world tumbled

over; people realized: something is going to happen and we have to do

something about it, otherwise it is going to go wrong. I followed it

very closely and I signed against the ITU proposal.”

Blunder

“The guys of the ASC (American Society of

Cinematographers) had lobbied for High Temporal Resolution; a

possibility for higher frame velocity in reproduction. Because 24

frames per second are of course unsufficient; a standard created around

1930, because the machines then couldn’t work faster”.

Director

of photography Kommer Kleijn S.B.C.

shooting 3D for a new Futuroscope Poitiers attraction

A

DCI (Digital Cinema Initiatives) –specification, is coming out, with

a new possible velocity of 48 a High Temporal Resolution. “How did they

get there?”,

wonders Kleijn. In an IBC-conference he walks over to meet participants

of DCI and asks them the reason. Their answers do not satisfy

him. “48 can be easily divided in 2, and then you get 24, they said".

So

if you film in 48 and throw away one out of two frames, then you can

still show it in a 24-cinema. But if you give me a camera that rolls

on 48, then I want to use the new possibilities in storytelling, and

then that will not work when seen at 24. So the possibility to reduce

to 24 is not actually really interesting. Finally, the 48 proposal was

a huge

blunder, because it also doesn’t work properly on DVD and blue ray.

Seven

American studios and the ASC had gone wrong.”

Digital Cinema Standardisation

Kleijn wants to

avoid the fixing of High Temporal Resolution on 48 at all costs.

Because he has become a member of a number of influential guilds, his

ideas are becoming increasingly heard. He receives an invitation to

participate at the Technical Module of the EDCF, an input organ for the

SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television

Engineers) DC28- committee, which had to define the standard for the

future digital film industry and projection. Unexpectedly he gets

involved with Imago, when he accompanies André Goeffers, president of

SBC (Belgian Society of Cinematographers), to a meeting in Paris.

Adreas Fischer-Hansen is then elected president and makes his vision of

the future known. One of his objectives is: Getting involved in digital

standardization. When he asks who would want to do this, Kleijn only

has to raise his hand. “I had already noticed that on my own,

changing the 48 frame rate was not going to work, but from inside

Imago, with the representation of 1400 cameramen, maybe it could. I

said immediately, 48 should become 60.”

Director

of photography Kommer Kleijn S.B.C. (photo:

Bart van Broekhoven)

Through a presentation about frame rates, during a meeting of

the

DC28-committee in Amsterdam, Kleijn gets very close to the fire. He

proposed to apply more flexibility in the new standard for digital

projection. “The whole standardization committee sat there yawning,

and afterwards it was very quiet. The Chairwoman, Wendy Aylsworth, now

Vice President of Technology by Warner Bros and Engineering Vice

President of SMPTE, suggested that a work group should be established.

“Who wants to volunteer?”, she asked. Me, of course. “Who is a

volunteer for Charing the group?” Again, silence. Then I raised my hand

again. All at once I was the Chairman of a workgroup of the

DC28-technical committee, and I was not even a member of the SMPTE yet.”

Bert Easey Technical Achievement Award

In

December 2009, Kleijn received the prestigious ‘Bert Easey Technical

Achievement Award’ from the British Society of Cinematographers. It was

in appreciation for his efforts that lead to the addition of the 60 fps

frame

rate in the international standard for digital projection. Even though

it has taken some years, finally, there are 6 standardized velocities

now:

24, 25, 30, 48, 50 and 60. “30 has been incorporated because in 3D

strobing bothers much more than in 2D. 48 is still there because you

need it to be able to project 24 in stereo. 50 to be able to see in 3D

in

25. The whole stereo community is of course interested in 60 frames per

second. The capacity of the machines to work with 30 frames per eye is

peanuts, you could say, but it does help. And if you shoot a film in

60, then you should also be able to show the 2D-version. For this

purpose you need 30. In the new standard 3D has gotten a solid place.

Kommer

Kleijn with Imago president Nigel Walters en B.S.C. member Joe Dunton

Does

he secretly hope to be asked to be the DoP of a feature film, now that

digital projection is on a good path? “I will always be very much in

love with the idea. But as a man of fifty without a lot of experience

in

that terrain, it is not very likely that I will be asked. Anyway,

I will not be upset about it, if that film

opportunity does not come about. Who knows, I might very soon make one

as a stereographer or 3d-consultant. Then I will assist a colleague,

which is also fine by me. Go with the flow.”

www.kommer.com

www.kommer.com/animoko

Translation from Dutch to English: Martijn Kraal

|